The Union is in the People: FW Ed Mann

Ed Mann’s life was a testament to the power of worker solidarity. His was a steel will set on struggle and defiance against overwhelming odds. Ed’s story is one of enduring the darkness of industrial collapse without losing hope.

Growing up in Toledo, Ed worked various intensive physical jobs. He was no stranger to tough, dangerous work. Ed remembered his mother inviting homeless folks for family meals. Despite having little, she showed deep solidarity with those around them. She also ensured Ed received a Reform Jewish education at a local temple. He never much identified with the religious side of his upbringing. Still, Ed valued his education for his whole life.

In 1952, Ed settled in Northeast Ohio. He started working full time in the local steel industry at the Brier Hill mill.

Things That Politicize People

Even with his Reform Jewish upbringing, racism was not a consistent issue in Ed’s personal life. Ed and American racism first clashed in 1947. One fateful day would define his future views on race and his organizing work. It started when he took out a YMCA membership.

Ed planned to exercise with his friend Bell, a Black man. Ed never considered that there were separate facilities for whites and Blacks. When Ed and Bell showed up together to work out, Ed asked for a guest pass. “Don’t cause any trouble,” the manager replied. “He’s got his YMCA and this is yours.”

“I think it’s things like that that politicize people,” he later reflected. “I was at an age where I was like a sponge, wanting to participate in society. Then I found out what society was like where I was living at that point in time.”

This shaped how he viewed the treatment of Black steelworkers in Ohio mills. The union locals had long stood by while bosses discriminated in pay and promotions. A key part of Ed’s early union years involved fights for equal treatment for his fellow workers. He later picketed with Black residents and unionists outside Akron against the KKK.

Putting Down Roots

Ed emphasized becoming active in the local community. “It’s so much easier to go somewhere else and demonstrate,” he noted, “than to demonstrate in your own home town.” Ed saw this quality as essential to good organizing. “You’ve got to put down roots if you want to change anything. You can’t be like a damn butterfly, flitting around all over.”

Years of gang-type work in the mills taught Ed what it meant to need someone’s help. Whether you liked another worker or not, “to get the job done and not die, you had to help each other.” It was this mutual necessity that led to firm trust. Ed could ask about workers’ kids or the type of car they drove. Eventually, someone would invite someone else over for a party or a beer. “Before you know it you’re friends. And then the politics started talking. That’s what I experienced.”

Ed wasn’t shy about his radical views despite pushback. “I found that the people didn’t really care what my politics were as long as I won grievances, did my job as a union officer.” By all accounts, he did. Ed bypassed contract procedures and fought grievance battles on the shop floor. He led many wildcat strikes, including one over his fellow worker Tony’s death.

Ed was smart about how he shared his political ideas. No radical efforts would amount to anything unless rooted in something real. “For me to have gone out to the gate and pass out the Socialist Workers Party newspaper, and not know anybody there, and expect to recruit thirty people by the end of the month, would have been insane!”

Ed’s actions spoke more than any labels. Not every radical was able to take the brutalities of the mills. “We saw many people come into the Brier Hill plant, real hotshots,” he said. “Every shade of the rainbow as far as radicals went, from fiery communist to whatever, but they couldn’t stay! They could run off at the mouth pretty good, write manifestos, but they couldn’t stay and do the job.”

The situation was simple: “We could express ourselves. We weren’t afraid of the boss. We were always thought of, ‘Hey, look at these radicals, look at these reds.’ But we would do our job. You got a job, you did it. You are not a slacker. You didn’t do any extra. You helped your fellow worker. Over the years you develop a certain credibility.”

Ed was friendly and open on principle at least as much by disposition. “If you’re going to be a socialist, you’ve got to be sociable,” he quipped. He built his organizing on quality shift work and worker accompaniment. He soon found himself a key player in United Steelworkers of America Local 1462.

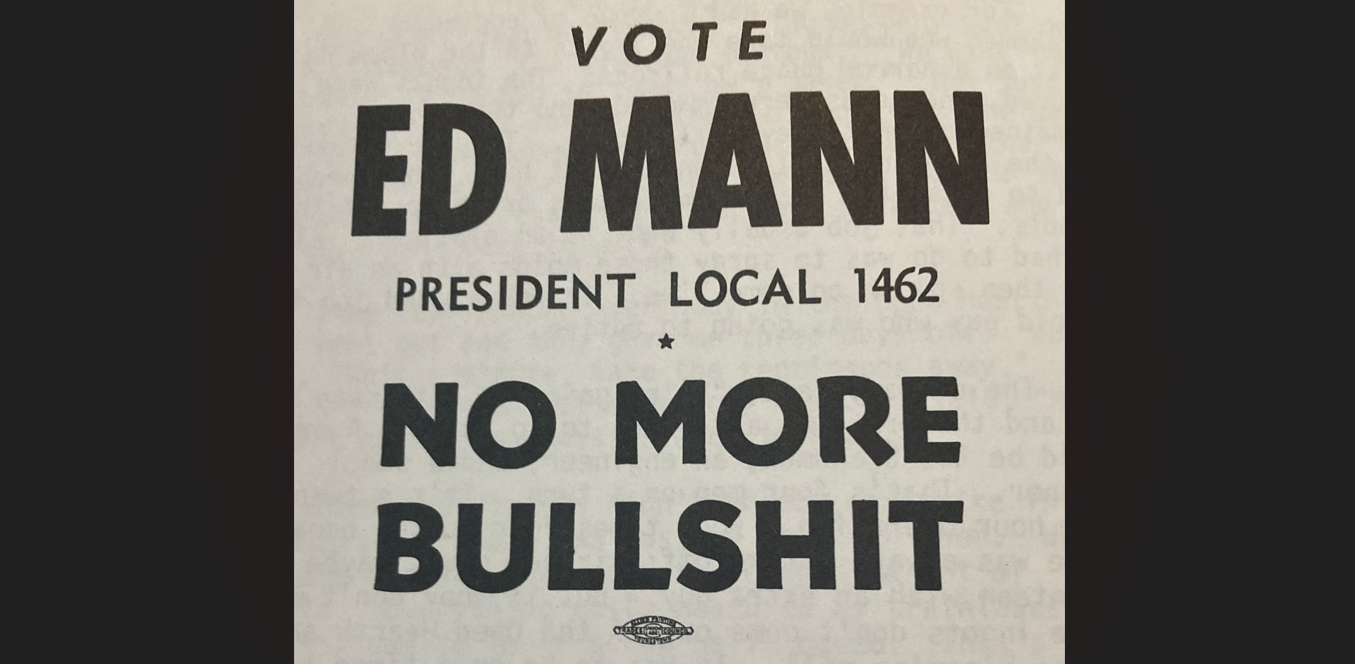

Against Bullshit

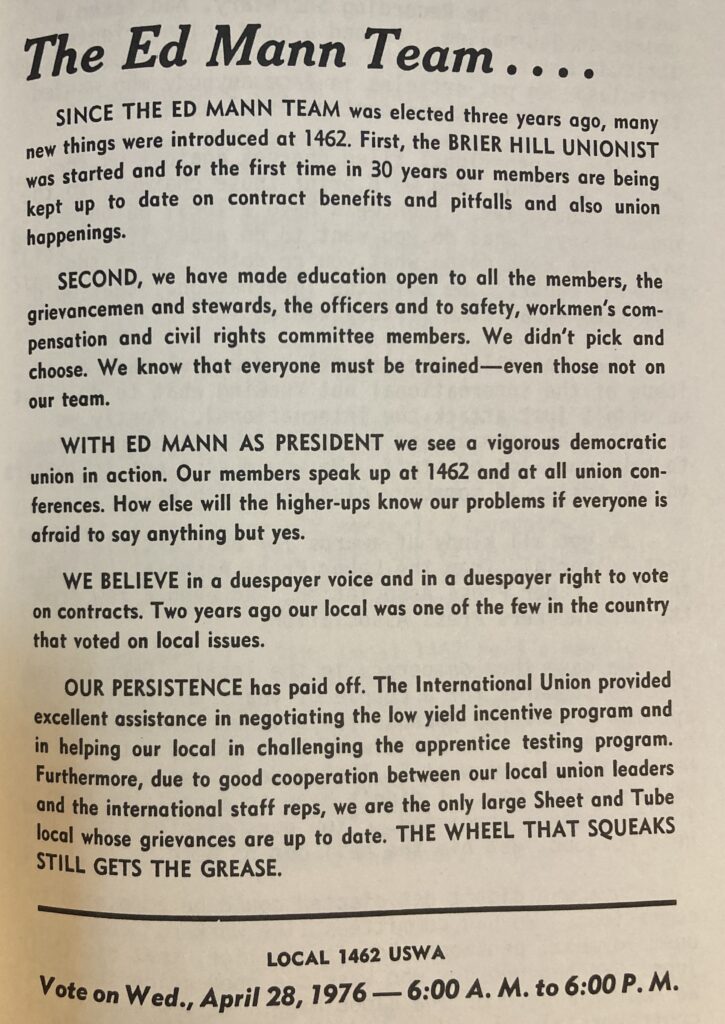

In 1973, USWA 1462 elected Ed as president. He was laser-focused on building democracy from the ground up. “We were trying to build a union in the plant, not worldwide,” he said. “We gave them democracy in the local.” He began an all-out assault on corruption. Before, officers had fixed elections. Union leadership had sided with the company in grievances. No more.

Ed helped establish the local’s first internal newsletter, the Brier Hill Unionist. The paper kept workers updated on all union activities and issues. Ed also opened union education to all members. He fought to enable the rank and file of the local to vote on contracts themselves. By 1976, Local 1462 could boast that it was the only large Sheet and Tube union with up-to-date grievances.

“I believe in direct action,” Ed declared. “Once a problem is put on paper and gets into the grievance procedure, you might as well kiss that paper goodbye.” Bosses could easily manipulate grievances. “When corporations started recognizing unions, they saw this,” he explained. “They co-opted the unions with the grievance procedure and the dues check-off. They quit dealing with the rank and file and started dealing with the people who wanted to be bosses like them.” These were the loathed “union bosses.”

Union leaders wielded contracts against rank and file as much as management. That led Ed to hold union contracts with employers in great suspicion. “I think we’ve got too much contract,” he admitted. “I think the IWW had a darn good idea when they said, ‘Well, we’ll settle these things as they arise.’”

Local organization was key to winning gains. The international union would dispute 1462’s proposed resolutions. The “Ed Mann Team” helped the local hold its ground. They caucused, handed out leaflets, and set good examples of solidarity. They won on every resolution. It was an “unheard-of defeat for the international union.” Ed began to reach out to other unions only once 1462 “functioned as a local, without all the petty bullshit.”

Local 1462’s revolutionary spirit was palpable by the steel mill shutdowns of 1979. Enraged by the Brier Hill mill closure, Steelworkers marched into Mahoning Country Club. They decided on a surprise confrontation with Sheet and Tube superintendent, Gordon Allen. Taken aback and embarrassed, Allen said, “Now, Ed, you know we are handling this through the Union.” With one voice the gathered workers replied, “WE ARE THE UNION!”

“I’m Going Down That Hill”

Ed Man addressing the decisive meeting of Local 1330 on January 28, 1980

On September 19, 1977, “Black Monday” terrorized locals. The sudden announcement that Youngstown Sheet and Tube would close was devastating. 5,000 workers were immediately out of a job. The local economy collapsed. In the next several years, U.S. Steel continued to shutter operations. 40,000 workers in manufacturing alone would lose their livelihoods. Youngstown still struggles in Black Monday’s long shadow.

People didn’t take it lying down. The community came together as workers began a fight for control of the local steel industry. Against the odds, Ed and countless others rallied workers. They fought for community ownership of the nearby abandoned Campbell works. But the company refused to negotiate.

Ed gave up on some arbitration process that would never come. Why couldn’t workers make the bosses sit down and talk? The idea was a long shot–but the only option he saw. Two months earlier, 300 Youngstown steelworkers joined with local supporters in Pittsburgh. They occupied the first two floors of U.S. Steel’s national headquarters. The occupation lasted for several hours. Ed decided that that tactic needed further exploration.

Ed was full of passion as he addressed Local 1330 the morning of January 28, 1980. “I’m going down that hill and I’m going into that building. And any one that doesn’t want to come along doesn’t have to but I’m sure there are those who’ll want to.” It would be a last stand.

At least 700 workers marched to the U.S. Steel office building downtown. The crowd met no resistance. The workers took over the building. When they reached the top floor, they found a secret executive game room. “My daughter Beth changed her baby’s diaper on the executives’ pool table,” Ed boasted. For most workers, it was the first time they had defied the establishment. “People were proud.”

Ed was proud, too. But the workers dispersed once the company agreed to negotiate a deal. Three days later, the company again refused to come to the table. Ed was honest in his analysis of the action. “At the end of the afternoon Bob Vasquez, president of Local 1330, decided to end the occupation. But if we had it to do again, I know that he, and I, and every one I know who was there, would have stayed in that building for as long as it took.”

Arrested at Trumbull Memorial Hospital

Ed was a staple at local pickets. He disliked that Youngstown public schools didn’t teach labor history. Ed would take his grandchildren with him on the picket line. It was here that he and fellow workers gave them an education about their working class heritage. In 1982, police brutalized and arrested him at a picket. He had joined with striking Trumbull Memorial Hospital workers.

Prosecutors charged Ed with inciting a riot and resisting arrest. He was found guilty and had to appeal all the way to the Ohio Supreme Court. “I found that the case had a very devastating effect,” he reflected. “I didn’t do very much . . . . For four years I think I was intimidated. You’re not getting any younger.”

But the union at Trumbull Hospital survived. AFSCME Local 2804 lives on to this day, almost 400 workers strong.

Lessons from the IWW

Ed Mann joined the IWW in 1984. He became a member after he had already retired. It’s easy for eager young radicals to overlook or even suspect older generations. But this breakdown of trust between age groups is yet another function of capitalism. Retired folks have much to offer a radical solidarity union. This is true for the IWW and others, like Ed’s Worker Solidarity Club. Ed’s story is an opportunity to remind ourselves: “young and old together, we shall not be moved.”

Ed joined the IWW out of principle. It didn’t matter that he had finished working. He was a true believer. Ed also joined with LTV retirees to save worker pensions after the company’s bankruptcy. The group called themselves “Solidarity USA.” Solidarity was by then the enduring theme of Ed Mann’s life and work.

What was it that Ed admired about the IWW? “The IWW is a lot like the Solidarity Club,” he said. “Whoever wants to do their thing at the moment, does it. If you want to participate, you participate, and if you don’t, you don’t.” Ed compared this to the mainstream unions. “The AFL-CIO is afraid of getting fined for violation of a contract, but if you don’t have a treasury, what the hell good is it going to do to fine you?”

Ed liked the IWW’s insistence “that workers should exercise some power.” He agreed workers must make decisions “instead of handing it over to bureaucrats.” He encouraged union members to demand more of the AFL-CIO, but he didn’t hold out much hope for it. “It’s not going to do its job. It’s not structured to do its job,” he mused. Ed didn’t think anything of the vertical boss-worker system of the trade unions. “I don’t regard the AFL-CIO as ‘the union.’ I think the union’s in the people.”

Ed advised being ready for the ‘right moment’ as key to success. Someone has to be laying the groundwork for the eventual class conflict. “Who knows what is going to make the workers say, ‘This is enough’? But the point is, somebody has to be there when they say, ‘This is enough!’”

Ed saw union contracts as an opening for corporate doublespeak and little else. Companies like to say they want workers to participate in management. Yet companies give away no real decision-making power. Labor contracts outline management rights, often for pages. But workers have no power in hiring, firing, disciplining, or the rules of production.

Ed saw the IWW’s vision as a more hopeful one for the future than the AFL-CIO model:

“The Wobblies say, ‘Do away with the wage system.’ For a lot of people that’s pretty hard to take. What the Wobblies mean is, you’ll have what you need. The wage system has destroyed us. If I work hard I’ll get ahead, but if I’m stronger than Jim over here, maybe I’ll get the better job and Jim will be sweeping floors. But maybe Jim has four kids. The wage system is a very divisive thing. It’s the only thing we have now, but it’s very divisive.

“Maybe I’m just dreaming but I think there’s a better way.”

Glimpses of a New World

Ed’s biggest labor actions are significant on their own merits. He democratized USWA 1462. He organized steel workers and community members to fight against the shutdowns. He put his body on the line for striking workers. But what makes them especially relevant to us is that they all happened before he was in our Union.

Ed’s story shows that the solidarity we need is already within the people we’re seeking to organize. It was in him before he joined us. His story also shows that the spirit of solidarity is not something limited to the shop floor. It can extend beyond into workers’ everyday lives. Just as the wage system shapes every part of our lives, so must solidarity.

From Ed, we can gain a focus on the tactical value of building concrete local power. Without it, no movement can ever become enough to build workers’ democracy. As Youngstown alone could not fight the steel industry bosses, no one community can build a new world on its own. But local communities can come together if they are willing and organized.

Nobody has found a substitute for the solidarity of the rank and file. That’s you and your coworkers, neighbors, and friends. Focus on the avenues for organization and solidarity right in front of you. There are paths open to you, closed to the rest of us. We all need you to help the work along right where you are.

Don’t get distracted by any bullshit.

References

You can learn more about FW Ed Mann and the fight to save Northeast Ohio’s steel mills in Staughton Lynd’s work, “The Fight Against Shutdowns: Youngstown’s Steel Mill Closings.” Ed is also featured alongside other Northeast Ohio workers in the short documentary film about the shutdowns, Shout Youngstown! Most facts about Ed’s life and all quotes are taken from a copy of his autobiography, “We Are the Union: The Story of Ed Mann” first given to me by Alice and Staughton Lynd. It is currently out of print.